Table of contents

This is part two (part one) of graph theory, focusing on “Small World Graphs”, with PowerShell based on (Chapter 3) of the excellent book Think Complexity 2e by Allen B. Downey (in fact I’d highly recommend any of the books in the “Think…” series some of which I might cover in future posts). The book and the book’s source (in Python) are available for free through the book’s webpage (the physical book can be purchased too).

Some necessary theory

Small World Graphs are graphs in which most nodes are not neighbours of one another, but the neighbors of any given node are likely to be neighbors of each other and most nodes can be reached from every other node by a small number of hops or steps.

Most people have heard of Small World Graphs in conjunction with the small-world experiment conducted by Stanley Milgram leading to the infamous phrase “six degrees of separation”.

We will try to replicate the experiment based on the work of Watts and Strogatz. The Watts-Strogatz model is a random graph generation model (we talked about random graphs in part one of this series) that produces graphs with small-world properties, i.e. short average path lengths and high clustering, which neither regular graphs (see below) nor random graphs exhibit at the same time.

-

Clustering is a measure of the degree to which nodes in a graph tend to group together. Evidence suggests that in most real-world networks, and in particular social networks, nodes tend to create tightly knit clusters characterized by a relatively high density of ties; this likelihood tends to be greater than the average probability of a tie randomly established between two nodes.

-

Average path-length - The average number of edges between two nodes.

-

Regular Graph - A graph where each node has the same number of neighbours the number of neighbours is also called the degree of the node.

The Watts and Strogatz model suggest the following steps to generate a Small World Graph:

- Start with a regular graph (a ring lattice graph can be used for this purpose) with n nodes and each node connected to k neighbours.

- Choose a subset of the edges and rewire them by replacing them with random edges.

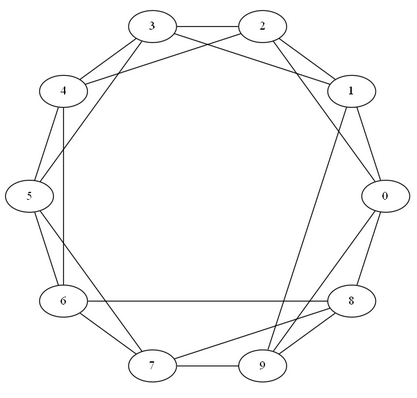

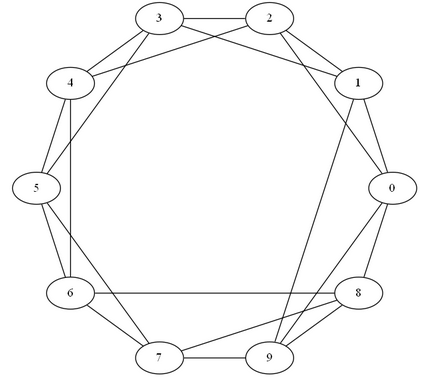

In a ring lattice graph the nodes are arranged in a circle with each node connected to the specified nearest neighbours.

Ring-Lattice graph

Enough theory let’s use some code. First, we’ll need some of the helper functions created in the first part.

Import-Module PSGraph

function Show-PSGraph ([ValidateSet('dot', 'circular', 'Hierarchical', 'Radial', 'fdp', 'neato', 'sfdp', 'SpringModelLarge', 'SpringModelSmall', 'SpringModelMedium', 'twopi')]$LayoutEngine = 'circular') {

$all = @($Input)

$tempPath = [System.IO.Path]::GetTempFileName()

$all | Out-File $tempPath

$new = Get-Content $tempPath -raw | ForEach-Object { $_ -replace "`r", "" }

$new | Set-Content -NoNewline $tempPath

Export-PSGraph -Source $tempPath -ShowGraph -LayoutEngine $LayoutEngine

Invoke-Item ($tempPath + '.png')

Remove-Item $tempPath

}

function New-Edge ($From, $To, $Attributes, [switch]$AsObject, [switch]$Undirected) {

$null = $PSBoundParameters.Remove('AsObject')

$ht = [Hashtable]$PSBoundParameters

if ($AsObject) {

return [PSCustomObject]$ht

}

return $ht

}

function Get-Neighbours ($Edges, $Name, [switch]$Undirected) {

$edgeObjects = @($Edges)

if (@($Edges)[0].GetType().FullName -ne 'System.Management.Automation.PSCustomObject') {

$edgeObjects = foreach ($edge in $Edges) {

[PSCustomObject]$edge

}

}

(& {

($edgeObjects.where{ $_.From -eq $Name }).To

if ($Undirected) {

($edgeObjects.where{ $_.To -eq $Name }).From

}

}).where{ ![String]::IsNullOrEmpty($_) }

}

function Get-LogSpace([Double]$Minimum, [Double]$Maximum, $Count) {

$increment = ($Maximum - $Minimum) / ($Count - 1)

for ( $i = 0; $i -lt $Count; $i++ ) {

[Math]::Pow( 10, ($Minimum + $increment * $i))

}

}

We create a helper function to generate a Ring-Lattice graph.

function Get-RingLattice($Nodes, $NumConnections){

$ht = [ordered]@{}

$ht.Nodes = $Nodes

$cons = [int]($NumConnections/2)

$len = $Nodes.Count

$ht.Edges = foreach ($node in $Nodes){

for ($i=$node+1;$i -le ($node+$cons);$i++){

New-Edge $node $Nodes[($i % $len)] -AsObject

}

}

$ht.Visual = graph {

inline 'edge [arrowsize=0]'

edge $ht.Edges -FromScript { $_.To } -ToScript { $_.From }

}

[PSCustomObject]$ht

}

Let’s create a Ring-Lattice graph with 10 nodes and 4 connections per node.

$ringLattice = Get-RingLattice (0..9) 4

$ringLattice.Visual | Show-PSGraph

Small-World Graphs (Watts-Strogatz)

To turn our Ring-Lattice graph into a small-world graph we need to “re-wire” the nodes. The algorithm for the re-wiring should follow this logic:

- Iterate over all edges and rewire them based on a specified probability.

- If an edge is chosen to be rewired

- Leave the .From part of the edge as is.

- Rewire the .To part of the edge to any random node, but…

- The current .From and To. nodes

- Any neighbours of the .From node

- Replace the current edge with the old .From and the new .To pair

We can re-use the Get-Neighbours function from my previous post.

function Get-SmallWorldGraph($Nodes, $NumConnections, $Probability){

$graph = Get-RingLattice $Nodes $NumConnections

$edges = $graph.Edges.Clone()

foreach ($edge in $graph.Edges){

$rand = (Get-Random -Minimum 0 -Maximum 10000) / 10000

if ($rand -le $Probability) {

$fromNeighbours = Get-Neighbours $graph.Edges $edge.From -Undirected

#need to use foreach construct to expand nexted array of fromNeighbours

$exclude = $edge.From,$edge.To,($fromNeighbours.foreach{$_})

$toConnect = $graph.Nodes.where{$_ -notin ($exclude.foreach{$_})}

#remove the current edge

#see https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/De_Morgan%27s_laws

$graph.Edges = $graph.Edges.where{$_.From -ne $edge.From -or $_.To -ne $edge.To}

#add the new edge += for "adding to an array is bad but good enough in this case

$graph.Edges += New-Edge $edge.From (Get-Random -InputObject $toConnect) -AsObject

}

}

#redo the visual part based on the new edges

$graph.Visual = graph {

inline 'edge [arrowsize=0]'

edge $graph.Edges -FromScript { $_.To } -ToScript { $_.From }

}

$graph

}

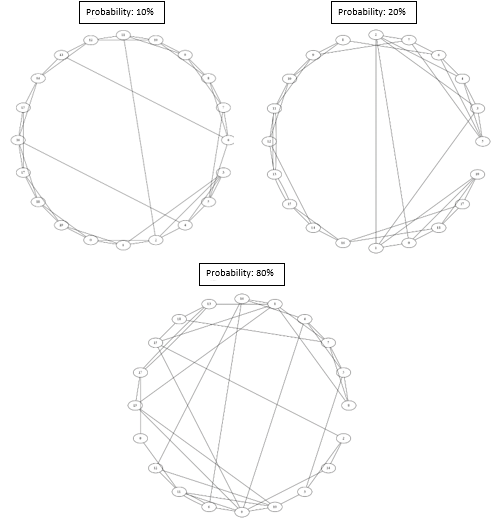

Below are three Small World graphs with the following properties:

- 20 nodes

- 4 connections per node

- Probabilities of 10%, 30%, and 80%

foreach ($prob in (.1,.2,.8)){

$swGraph = Get-SmallWorldGraph (0..19) 4 $prob

$swGraph.Visual | Show-PSGraph

}

As a next step, we need to develop methods that help us to evaluate the clustering and path-length properties of the produced graphs.

Clustering Coefficient

A cluster can be defined as a set of nodes with edges between all pairs of nodes in the set. The clustering coefficient for a node is given by the proportion of actual links between the nodes within its neighbourhood divided by the number of links that could possibly exist between them. If we iterate over every node of a graph and calculate this proportion and take the average of those, we are getting the Clustering coefficient for the graph.

The number of unique connections between a set of n nodes can be calculated with the formula $\frac{n(n-1)}{2}$.

If you imagine a room with n people, where you want to determine the number of unique pairs:

- The first person can pair up with everyone except themselves n-1..

- …so can everyone else n*(n-1).

- Since n represents the number of people rather than pairs the result needs to be divided by 2 $\frac{n(n-1)}{2}$.

Below is the implementation of the clustering coefficient algorithm.

function Get-ClusteringCoefficient ($Graph){

$individualCEs = foreach ($node in $Graph.Nodes){

$neighbours = Get-Neighbours $Graph.Edges $node -Undirected

$numNeighbours = $neighbours.Count

#CE undefined skip to next node

if ($numNeighbours -lt 2) {

[Single]::NaN

continue

}

$possibleConnections = $numNeighbours * ($numNeighbours -1) / 2

$nodes = $Graph.Nodes

$actualConnections = for ($i = 0; $i -lt $numNeighBours; $i++) {

for ($j = 0; $j -lt $neighbours.Count; $j++) {

if ($i -lt $j) {

$l = $neighbours[$i]

$r = $neighbours[$j]

#the way the edge objects are setup currently we will need to check for both sides

#would be better to setup sundirected edges differently

$Graph.Edges.where{($_.From -eq $l -and $_.To -eq $r) -or ($_.From -eq $r -and $_.To -eq $l) }

}

}

}

($actualConnections.Count/$possibleConnections)

}

#return the average of the clustering coefficients per node exlcuding NaNs

($individualCEs.where{-not ([Single]::IsNaN($_)) } | Measure-Object -Average).Average

}

If we test with our Ring-Lattice graph from our, we can get the expected .5 (each nodes has 4 neighbours with 3 connections out of possible 6 connections)

Get-ClusteringCoefficient $ringLattice

0.5

Shortest Path Length

The next step is to calculate the shortest path length, which is the average length of the shortest path between each pair of nodes.

There are several well-known algorithms to do this one of them is the Dijkstra algorithm. The algorithm is based on breadth-first search which means that the search starts with the immediate neighbours of a node before traversing deeper into the graph by looking at the neighbour’s neighbours and so on. We can use a simplified version of the Dijkstra algorithm since we are dealing with undirected graphs where each edge has an equal weight.

At a high level, the algorithm works like this:

- We make use of .Net’s built-in LinkedList collection to simulate a stack (add at the end) and queue behaviour (remove from the beginning) to traverse through the nodes of the graph in breadth-first manner.

- A HashTable is used to keep track of each node’s distance to the provided start node.

Get-Neighboursis used to retrieve the immediate neighbours of the current node (starting with the start node).- For those neighbours, that we are not already keeping track of.

- Update the neighbour’s distance to 1 + the distance of the current node (since the distance to the neighbour is, by defintion, one more than the current node’s distance)

- We add the neighbour to the linked list in order to traverse one level further.

- At then end an object with source (the start node), destination, and distance properties is returned containing the distance’s for each node in the graph to the specified start node.

function Get-ShortestPath ($Graph, $StartNode) {

#distances keeps track of distances from the start node for each node

$distances = @{$StartNode = 0}

#usage of linked list to be able to add at the end (like in a stack) and remove from the beginning (like in a queue)

$list = New-Object System.Collections.Generic.LinkedList[int]

$null = $list.AddFirst($StartNode)

while ($list.Count -gt 0) {

#get the first element from the linked list

$node = $list.First.Value

$null = $list.RemoveFirst()

$neighbours = Get-Neighbours $Graph.Edges $node -Undirected

#find the neighbours that are not already contained in the hashtable

$neighbours = $neighbours.where{ $_ -notin $distances.Keys }

foreach ($neighbour in $neighbours){

#the distance to the neighbour is, by defintion, the current node's distance + 1

$distances.$neighbour = $distances.$node + 1

#add the neighbour to the list to discover further connections

$null = $list.AddLast($neighbour)

}

}

$distances.GetEnumerator().foreach{

[PSCustomObject][ordered]@{

Source = $startNode

Destination = $_.Name

Distance = $_.Value

}

}

}

The function returns an object array with Source, Distance, and Destination properties. If we use it on the first node of a our previously created Ring-Lattice graph (added here again for convenience), we get the following result:

Get-ShortestPath $ringLattice 0

Source Destination Distance

------ ----------- --------

0 9 1

0 8 1

0 7 2

0 6 2

0 5 3

0 4 2

0 3 2

0 2 1

0 1 1

0 0 0

To get the average shortest path length for a whole graph we need to … :

- … do this for every unique starting point (From) in the graph.

- Remove the 0 distance entries (from node to self).

- Get the average of the remaining distances.

$groupedEdges = $ringLattice.Edges | group From

$distances = foreach ($group in $groupedEdges){

Get-ShortestPath $ringLattice $group.Name

}

($distances.where{$_.Distance -ne 0 -and $_.Distance} |

Measure-Object -Property Distance -Average).Average

1.66666666666667

Small-World experiment (Watts, Strogatz)

Great, now we have everything in place to do duplicate the Small-world experiment. Showing that there are Small-Word graphs with a certain range of probability (for re-wiring) with high clustering-coefficients (like regular graphs) and a short average path lengths (like in random graphs).

In practice it turned out that, at least with the sloppy version of my code, the PowerShell functions are not executing nearly fast enough to carry out the experiment with 1000 nodes for each graph and 10 connections each. Even though I have added multi-threading to the Shortest-Path parts using PSThreadJobs’s Start-ThreadJob function since this is definitely the bottleneck.

function Do-Experiment ($Nodes = (0..99), $NumConnections=3, $Probabilities){

foreach ($probability in $Probabilities){

$apl = [System.Collections.ArrayList]@()

$ccoe = [System.Collections.ArrayList]@()

$jobs = @()

$graph = Get-SmallWorldGraph $Nodes $NumConnections $probability

$groupedEdges = $graph.Edges | group From

foreach ($group in $groupedEdges){

$initBlock = [ScriptBlock]::Create(

'function Get-ShortestPath{' + (Get-Command Get-ShortestPath).Definition + '}' +

'function Get-Neighbours{' + (Get-Command Get-Neighbours).Definition + '}'

)

$jobs += Start-ThreadJob -InitializationScript $initBlock {

$group = $using:group

Get-ShortestPath $using:graph $group.Name

}

}

$null = $jobs | Wait-Job

$distances = $jobs | Receive-Job

$null = $jobs | Remove-Job

$null = $apl.Add(($distances.where{$_.Distance -ne 0} |

Measure-Object -Property Distance -Average).Average)

$null = $ccoe.Add((Get-ClusteringCoefficient $graph))

[PSCustomObject][ordered]@{

Probability = $probability

AveragePathLength = ($apl | Measure-Object -Average).Average

ClusteringCoeeficient = ($ccoe | Measure-Object -Average).Average

}

}

}

#get log-spaced probabilites to simulate the experiment with the same parameters

$probabilities = Get-LogSpace -4 0 9

$result = Do-Experiment -Probabilities $probabilities

#scale the avg. path length and clustering coeff.

#to be able to plot them on the same axis (same as in the experiment)

$firstApl = $result[0].AveragePathLength

$firstCoeff = $result[0].ClusteringCoeeficient

for ($i=0;$i -lt $result.Count;$i++){

$result[$i].AveragePathLength = $result[$i].AveragePathLength/$firstApl

$result[$i].ClusteringCoeeficient = $result[$i].ClusteringCoeeficient/$firstCoeff

}

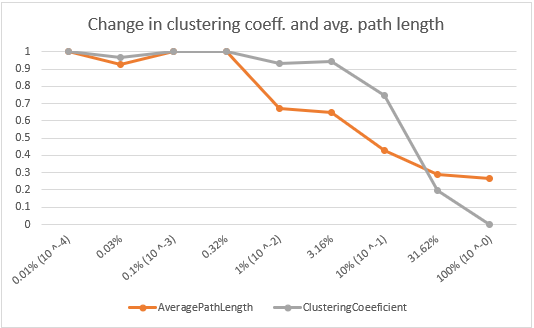

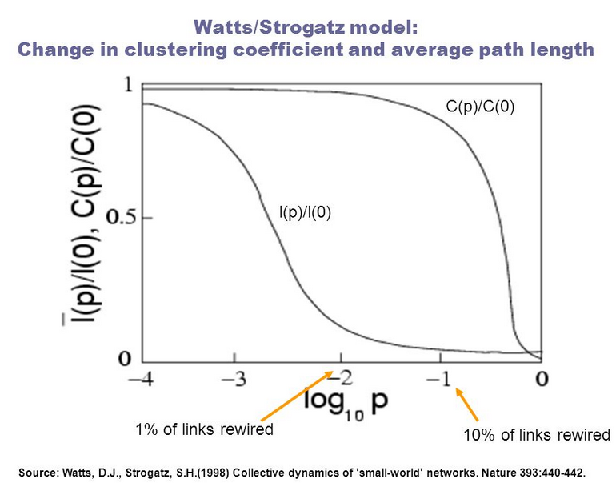

While this is unfortunate, the results for 100 nodes with 3 connections (see first graph below) are showing a similar trend as the original study’s results from the Watts/Strogatz paper (L = average path length standardized, C = clustering coefficients standardized).As the probability increases, the average path length decreases quite rapidly because even a small number of randomly rewired edges provide shorter paths between nodes that are far apart. Replacing neighbouring links decreases the clustering coefficient much more slowly. As a result, there is a wide range of probabilities with high clustering coefficients and low average path lengths.